If you’ve been drawn to this site through a love of guns or dogs you might find a passion for trapping a bit eccentric, or even a bit bizarre. So please allow me, if you will, a couple of hundred words to try and explain just how important traps are in the greater scheme of things. I hope I’ll convince you, and maybe even convert you.

The things that makes Homo sapiens special, the things that makes us unique, the very things that set us apart from all the other animals started a long, long time ago with the first ever trap.

“What about spiders?” You might ask. “They use traps, they were here before us, and there’s nothing particularly special about them.”

I would argue that spiders’ webs aren’t traps, just air-hung nets fishing for flies, no different than the flowing filaments of a mindless jelly fish.

“Ant lions then? They dig pit traps.”

Again no. Ants would walk, with impunity, in and out of these pits if the little monsters were not sitting at the bottom flicking sand at them. There’s no skill involved there.

“Venus Fly Traps?”

Ah, well there you may have me. But whatever ancient, unfathomable intellect conspired to transform a plant’s leaves into gin-traps will have theologians and philosophers arguing until the end of days. It’s simply on a different level to this story.

A trap is not simply a tool; ape men’s spears and hand axes were tools, and little more than sticks and stones, they don’t define humanity. Thrushes use tools, so do crows, so do monkeys. No, it was the earliest traps that gave humanity that vital jump start.

Maybe the first trap was a huge pit, bristling with flint topped stakes, designed to catch a bison, or a mammoth, or a sabre toothed tiger! More likely it was a simple snare or a precariously balanced rock. The point is; as soon as that first treadle tipped open, or cord tightened or rock dropped, the world changed and something new was born; strategy, technology, humanity!

Only one species could comprehend the significance of a foot print in the mud or snow. Only one species could read it, form a plan, set a trap and now catch their pray from the safety of their own cave, feed themselves, feed their families, even feed their whole clan.

Now not only the biggest and the fiercest survived. No longer did a man have to be the fastest, or strongest, or be a crack shot with spears or stones to win a meal. With traps came not only strategy, technology and humanity, but also society.

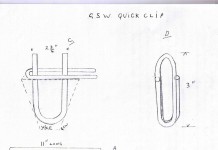

As I’m writing this article, thousands of years later and possibly on a different continent to that first trap, I have some of its distant descendents on the bench next to me. The closest one, if you’re interested, is a Fen MK6, of the sub-order: Sprung kill-traps. It’s not the most inspiring piece of human ingenuity, particularly when compared to later inventions like rifles, or aircraft, or the Large Hadron Collider, but it serves its purpose, and it does so very well. It’s strong enough to kill a rabbit and sensitive enough to trap a rat.

My trap can still feed me: either directly through catches, or as a part of gainful employment. What is more; my trap has been ordered ‘Approved’ by the British government; quite literally licensed to kill! It has sprung through the legislative hoops held out to appease the outcry of a childish public’s anti-trapping squeamishness (part, I believe, of the larger epidemic of cerebral infantilisation that now seems to be sweeping though our towns and cities). In the eyes of the law my trap is as ethical a way to end a life as an abattoir’s bolt gun or a kosher butcher’s blade.

Even in today’s nannying blizzard of safety regulations, when you push a trap’s jaws apart you can feel it push back. It could easily break your skin, or even your fingers, but you can’t be scared of it, no more than you could be scared of your own dogs and still expect them to work for you. Like a wise man once said ‘there’s an ocean of difference between fear and respect’. Respect traps, they’ve earned it, and if you obey their rules they’ll never bite you.

So take traps seriously, use them thoughtfully, set them carefully, and they become more than mere tools. They become your workmates, your hunting partners and eventually your old friends.